I am a big fan of Adrian Sherwood's passion for luring the greatest luminaries in Jamaican music history into late-career collaborations, as it is hard to imagine a better deal than working with On-U Sound's murderers' row of killer musicians and having a contemporary dub visionary at the console. Midnight Rocker (released in April) was the first fruit of Sherwood's union with Horace Andy and (unsurprisingly) focuses primarily on Andy's legendary voice while putting a new spin on a few of the Jamaican tenor's signature jams (along with a nod to his more recent work with Massive Attack). Given the caliber of everyone involved, Rocker is a predictably likable album and an impressive return for Andy, but a big part of the fun with classic Jamaican music is the inevitable wave of dubs and variations that follow, so I connected much more deeply with the newly released companion album, Midnight Scorchers. Wisely, Andy's voice remains a central focus, so it is easy to recognize the hooks and melodies from the previous album in their new context, yet Sherwood allows himself to go a bit wild in the studio for a "sound system" take on the material. To my ears, the same songs are the strongest on both albums, but the weaker songs from Rocker benefit significantly from the more adventurous arrangements and production on Scorchers.

Midnight Rocker borrows its title from the opening line of Massive Attack's "Safe From Harm," which was the lead song on their 1991 debut Blue Lines. Notably, that album was the beginning of Andy's recurring involvement with that project, but "Safe From Harm" is a curious song to revisit, as Andy did not sing on the original and it has a darker, more dramatic tone than the rest of Midnight Rocker. Given how wildly successful that album was, I imagine its inclusion here was a savvy choice, but its killer bass and tambourine groove plays far more to Sherwood's strengths than the lyrics and tone do to Andy's. The album's other trips down memory lane are a handful of contemporized resurrections from Andy's own sprawling discography such as "This Must Be Hell, "Materialist," and "Mr. Bassie." Of that lot, "Mr. Bassie" fares the best, as it boasts a strong melodic hook and wades into increasingly dubby territory as it unfolds.

Midnight Rocker borrows its title from the opening line of Massive Attack's "Safe From Harm," which was the lead song on their 1991 debut Blue Lines. Notably, that album was the beginning of Andy's recurring involvement with that project, but "Safe From Harm" is a curious song to revisit, as Andy did not sing on the original and it has a darker, more dramatic tone than the rest of Midnight Rocker. Given how wildly successful that album was, I imagine its inclusion here was a savvy choice, but its killer bass and tambourine groove plays far more to Sherwood's strengths than the lyrics and tone do to Andy's. The album's other trips down memory lane are a handful of contemporized resurrections from Andy's own sprawling discography such as "This Must Be Hell, "Materialist," and "Mr. Bassie." Of that lot, "Mr. Bassie" fares the best, as it boasts a strong melodic hook and wades into increasingly dubby territory as it unfolds.

Back in 2009, Important Records released a landmark compilation entitled The Harmonic Series (A Compilation Of Musical Works In Just Intonation). Significantly, that album featured a Greg Davis piece entitled "Star Primes (For James Tenney)," which was Davis's earliest foray into composing using just intonation. Nearly a decade later, greyfade founder Joseph Branciforte found himself mesmerized by that piece on a long drive back home from Vermont and was inspired to contact Davis to discuss the unusual process behind the piece. As it turns out, Davis's interest in mathematical just intonation experiments ran quite deeply, as it formed the entire basis for his 2009 album Primes. Naturally, the enthusiastic Branciforte encouraged Davis to revisit his work in that vein, which led to an 8-channel performance at NYC's Fridman Gallery in 2019. The aptly titled New Primes is a reworking of that new material repurposed for a stereo home-listening experience. Needless to say, math-driven sine wave drones are not for everyone, but the cold and futuristic alien beauty of these pieces will likely resonate deeply with fans of otherworldly "ghost in the machine" opuses like Nurse With Wound's Soliloquy For Lilith.

Back in 2009, Important Records released a landmark compilation entitled The Harmonic Series (A Compilation Of Musical Works In Just Intonation). Significantly, that album featured a Greg Davis piece entitled "Star Primes (For James Tenney)," which was Davis's earliest foray into composing using just intonation. Nearly a decade later, greyfade founder Joseph Branciforte found himself mesmerized by that piece on a long drive back home from Vermont and was inspired to contact Davis to discuss the unusual process behind the piece. As it turns out, Davis's interest in mathematical just intonation experiments ran quite deeply, as it formed the entire basis for his 2009 album Primes. Naturally, the enthusiastic Branciforte encouraged Davis to revisit his work in that vein, which led to an 8-channel performance at NYC's Fridman Gallery in 2019. The aptly titled New Primes is a reworking of that new material repurposed for a stereo home-listening experience. Needless to say, math-driven sine wave drones are not for everyone, but the cold and futuristic alien beauty of these pieces will likely resonate deeply with fans of otherworldly "ghost in the machine" opuses like Nurse With Wound's Soliloquy For Lilith. I doubt anyone can truly say that they know what to expect from a new Hausu Mountain release, but I still felt a bit gobsmacked by the latest from this ambitiously unhinged Ohio duo. While it may read like hyperbole to the uninitiated, the label's claim that Whipped Stream is a "durational smorgasbord of new music capable of knocking even the most seasoned zoner onto their ass" feels like an apt description of this triple cassette behemoth of fried and kaleidoscopic derangement (it clock in at roughly 3½ hours, after all). As I have not yet been lucky enough to experience Moth Cock's cacophonous sensory onslaught live, I was also a bit stunned to learn that most or all these pieces were culled from real-time performances. I honestly do not comprehend how two guys armed with a sax, loop pedals, and a "decades-old Electribe sampler / drum machine" can whip up such a vividly textured and wildly imaginative hurricane of sound so quickly and organically, as there seems to be some real hive mind shit afoot with these dudes. Unsurprisingly, I am at a loss to find a succinct description to explain what transpires over the course of this singular opus, but most of Whipped Stream can be reasonably described as a gnarled psychedelic freakout mashed together with Borbetomagus-style free jazz, the '80s noise tape underground, and jabbering sound collage lunacy. In the wrong hands, such an outré stew coupled with such an indulgent duration would be an effective recipe for total unlistenability, but I'll be damned if Moth Cock have not emerged from this quixotic endeavor looking like fitfully brilliant visionaries. I should add the caveat that Moth Cock also seem willfully annoying at times, but it is rare that such bumps in the road are not ultimately transformed into a near-perfect mindfuck or something unexpectedly sublime.

I doubt anyone can truly say that they know what to expect from a new Hausu Mountain release, but I still felt a bit gobsmacked by the latest from this ambitiously unhinged Ohio duo. While it may read like hyperbole to the uninitiated, the label's claim that Whipped Stream is a "durational smorgasbord of new music capable of knocking even the most seasoned zoner onto their ass" feels like an apt description of this triple cassette behemoth of fried and kaleidoscopic derangement (it clock in at roughly 3½ hours, after all). As I have not yet been lucky enough to experience Moth Cock's cacophonous sensory onslaught live, I was also a bit stunned to learn that most or all these pieces were culled from real-time performances. I honestly do not comprehend how two guys armed with a sax, loop pedals, and a "decades-old Electribe sampler / drum machine" can whip up such a vividly textured and wildly imaginative hurricane of sound so quickly and organically, as there seems to be some real hive mind shit afoot with these dudes. Unsurprisingly, I am at a loss to find a succinct description to explain what transpires over the course of this singular opus, but most of Whipped Stream can be reasonably described as a gnarled psychedelic freakout mashed together with Borbetomagus-style free jazz, the '80s noise tape underground, and jabbering sound collage lunacy. In the wrong hands, such an outré stew coupled with such an indulgent duration would be an effective recipe for total unlistenability, but I'll be damned if Moth Cock have not emerged from this quixotic endeavor looking like fitfully brilliant visionaries. I should add the caveat that Moth Cock also seem willfully annoying at times, but it is rare that such bumps in the road are not ultimately transformed into a near-perfect mindfuck or something unexpectedly sublime. This is apparently B. Fleischmann's eleventh solo album, which surprised me a bit, as I generally enjoy his work yet have only heard a small fraction of it. That said, the eclectic and shapeshifting Austrian composer's release schedule has slowed considerably since the heyday of IDM/indietronica/glitch pop in the late '90s/early 2000s that put him on the map. In fact, it has been four years since Fleischmann last surfaced with the amusingly titled but hopefully not prophetic Stop Making Fans and Music for Shared Rooms is actually more of a retrospective than a formal new statement. That said, most fans (myself included) are unlikely to have previously encountered any of the sixteen pieces collected here, as the album is a look back at some highlights from Fleischmann's extensive archive of pieces composed for film and theater. That archive apparently includes roughly 600 pieces composed over a stretch of twelve years, so Fleischmann presumably did not have much trouble coming up with a double LP worth of delights. To his credit, however, he decided to rework and recontextualize the selected pieces into a satisfying and thoughtfully constructed whole (and one that also doubles as a "kaleidoscopic glimpse of a forward-thinking musician at home in many different musical worlds"). Admittedly, some of those musical worlds appeal more to me than others, but Fleischmann almost always brings a strong pop sensibility and bittersweet warmth to the table, so the results are invariably wonderful when he hits the mark (which he does with impressive frequency here).

This is apparently B. Fleischmann's eleventh solo album, which surprised me a bit, as I generally enjoy his work yet have only heard a small fraction of it. That said, the eclectic and shapeshifting Austrian composer's release schedule has slowed considerably since the heyday of IDM/indietronica/glitch pop in the late '90s/early 2000s that put him on the map. In fact, it has been four years since Fleischmann last surfaced with the amusingly titled but hopefully not prophetic Stop Making Fans and Music for Shared Rooms is actually more of a retrospective than a formal new statement. That said, most fans (myself included) are unlikely to have previously encountered any of the sixteen pieces collected here, as the album is a look back at some highlights from Fleischmann's extensive archive of pieces composed for film and theater. That archive apparently includes roughly 600 pieces composed over a stretch of twelve years, so Fleischmann presumably did not have much trouble coming up with a double LP worth of delights. To his credit, however, he decided to rework and recontextualize the selected pieces into a satisfying and thoughtfully constructed whole (and one that also doubles as a "kaleidoscopic glimpse of a forward-thinking musician at home in many different musical worlds"). Admittedly, some of those musical worlds appeal more to me than others, but Fleischmann almost always brings a strong pop sensibility and bittersweet warmth to the table, so the results are invariably wonderful when he hits the mark (which he does with impressive frequency here). This first solo album from queer, androgynous soul singer Kyle Kidd is an incredibly strong contender for best debut of the year, but he/she/they (Kidd embraces all pronounds) has been been steadily releasing great music for a while as part of Cleveland's Mourning [A] BLKstar ensemble. Notably, however, Kidd's past also includes a background in church choirs as well as a stint as an American Idol competitor. Normally learning about the latter would send me running in the opposite direction, but Kidd joins the exclusive pantheon of vocal virtuosos like Ian William Craig and Zola Jesus lured away from a conventional trajectory by a healthy passion for more underground sounds. That said, a decent amount of Soothsayer legitimately feels like it could have burned up the Soul/R&B charts if it had been released in the late '70s and had a major label production team at the console. As time travel was not a viable option, Soothsayer instead found a home on the oft-stellar Chicago indie American Dreams and Kidd's sensuous, hook-filled songs eschew the polished sheen of pop production for a hypnagogic veil of tape hiss and reverb (much to my delight, predictably).

This first solo album from queer, androgynous soul singer Kyle Kidd is an incredibly strong contender for best debut of the year, but he/she/they (Kidd embraces all pronounds) has been been steadily releasing great music for a while as part of Cleveland's Mourning [A] BLKstar ensemble. Notably, however, Kidd's past also includes a background in church choirs as well as a stint as an American Idol competitor. Normally learning about the latter would send me running in the opposite direction, but Kidd joins the exclusive pantheon of vocal virtuosos like Ian William Craig and Zola Jesus lured away from a conventional trajectory by a healthy passion for more underground sounds. That said, a decent amount of Soothsayer legitimately feels like it could have burned up the Soul/R&B charts if it had been released in the late '70s and had a major label production team at the console. As time travel was not a viable option, Soothsayer instead found a home on the oft-stellar Chicago indie American Dreams and Kidd's sensuous, hook-filled songs eschew the polished sheen of pop production for a hypnagogic veil of tape hiss and reverb (much to my delight, predictably). Over the last few years, it has become quite clear to me that any major new solo guitar album from Bill Orcutt is destined to be an inventive, visceral, and damn near essential release. Unsurprisingly, Music for Four Guitars does absolutely nothing to disrupt that impressive run, yet I sometimes forget that Orcutt has a restless creative streak that endlessly propels him both outward and forward like some kind of avant garde shark. As a result, his discography is full of wild surprises, unexpected detours, and challenging experiments such as last year's wonderfully obsessive and completely bananas A Mechanical Joey, so anyone who thinks they know exactly what to expect from a new Bill Orcutt album is either delusional or not paying close enough attention. Case in point: Music for Four Guitars feels like an evolution upon Orcutt's Made Out of Sound approach of using a second track to improvise against himself, but he now expands it to four tracks and shifts to a more composed, focused, and melodic approach very different from his volcanic duo with Chris Corsano. Notably, this project was originally intended for a Rhys Chatham-esque quartet of guitarists and has been gestating since at least 2015, but COVID-era circumstances ultimately led Orcutt to simply do everything himself. As Tom Carter insightfully observes in the album notes, this album is a fascinating hybrid of the feral spontaneity of Orcutt's guitar albums and the "relentless, gridlike composition" of his electronic music that often calls to mind an imaginary Steve Reich-inspired post-punk/post-hardcore project from Touch and Go or Amphetamine Reptile's heyday.

Over the last few years, it has become quite clear to me that any major new solo guitar album from Bill Orcutt is destined to be an inventive, visceral, and damn near essential release. Unsurprisingly, Music for Four Guitars does absolutely nothing to disrupt that impressive run, yet I sometimes forget that Orcutt has a restless creative streak that endlessly propels him both outward and forward like some kind of avant garde shark. As a result, his discography is full of wild surprises, unexpected detours, and challenging experiments such as last year's wonderfully obsessive and completely bananas A Mechanical Joey, so anyone who thinks they know exactly what to expect from a new Bill Orcutt album is either delusional or not paying close enough attention. Case in point: Music for Four Guitars feels like an evolution upon Orcutt's Made Out of Sound approach of using a second track to improvise against himself, but he now expands it to four tracks and shifts to a more composed, focused, and melodic approach very different from his volcanic duo with Chris Corsano. Notably, this project was originally intended for a Rhys Chatham-esque quartet of guitarists and has been gestating since at least 2015, but COVID-era circumstances ultimately led Orcutt to simply do everything himself. As Tom Carter insightfully observes in the album notes, this album is a fascinating hybrid of the feral spontaneity of Orcutt's guitar albums and the "relentless, gridlike composition" of his electronic music that often calls to mind an imaginary Steve Reich-inspired post-punk/post-hardcore project from Touch and Go or Amphetamine Reptile's heyday. In 1965, sixteen-year-old Isabel Baker stepped into a recording studio with some session musicians, and two days later emerged with what could be considered the very first Christian rockabilly album, if not the only one of its kind. I've never heard anything like it.

In 1965, sixteen-year-old Isabel Baker stepped into a recording studio with some session musicians, and two days later emerged with what could be considered the very first Christian rockabilly album, if not the only one of its kind. I've never heard anything like it.  I had successfully deluded myself into thinking that I had spent my pandemic downtime wisely and constructively for the most part, but learning that Drew Daniel spent that same period assembling an all-star disco ensemble is now making me lament the sad limitations of my imagination and ambition. The resultant album—Is It Going to Get Any Deeper Than This?—is slated for release this October, but this teaser mini-album (part of Thrill Jockey's 30th anniversary campaign of limited/special releases) is one hell of a release in its own right and a true jewel in Daniel's discography. Naturally, the big immediate draws are the killer single "Is It Gonna to Get Any Deeper Than This (Dark Room Mix)" and a disco/deep house reimagining of Coil's classic "The Anal Staircase," but the other two songs are every bit as good (if not better) than that pair, so no self-respecting fan of Daniel's oeuvre will want to sleep on this ostensibly minor release (very few artists choose to release their best work on cassingle in 2022). Naturally, there is plenty of psychotropic weirdness mingled with all the great grooves, but I was still legitimately taken aback by how beautifully Daniels and his collaborators shot past kitsch/homage/pastiche and landed at completely functional, fun, and legit dance music. No one would raise a quizzical eyebrow if someone secretly slipped this album into the playlist at a party (not until "Anal Staircase" dropped, at least).

I had successfully deluded myself into thinking that I had spent my pandemic downtime wisely and constructively for the most part, but learning that Drew Daniel spent that same period assembling an all-star disco ensemble is now making me lament the sad limitations of my imagination and ambition. The resultant album—Is It Going to Get Any Deeper Than This?—is slated for release this October, but this teaser mini-album (part of Thrill Jockey's 30th anniversary campaign of limited/special releases) is one hell of a release in its own right and a true jewel in Daniel's discography. Naturally, the big immediate draws are the killer single "Is It Gonna to Get Any Deeper Than This (Dark Room Mix)" and a disco/deep house reimagining of Coil's classic "The Anal Staircase," but the other two songs are every bit as good (if not better) than that pair, so no self-respecting fan of Daniel's oeuvre will want to sleep on this ostensibly minor release (very few artists choose to release their best work on cassingle in 2022). Naturally, there is plenty of psychotropic weirdness mingled with all the great grooves, but I was still legitimately taken aback by how beautifully Daniels and his collaborators shot past kitsch/homage/pastiche and landed at completely functional, fun, and legit dance music. No one would raise a quizzical eyebrow if someone secretly slipped this album into the playlist at a party (not until "Anal Staircase" dropped, at least). There are several William Basinski albums that I absolutely love, but his various collaborations are rarely as compelling as his solo work (the leftfield Sparkle Division being a notable exception, of course). The fundamental issue is that Basinski's finest moments tend to be an intimate distillation of a single theme to its absolute essence, which does not leave much room at all for anyone else to add something without dispelling the fragile magic. While it is unclear if Janek Schaefer is unusually attuned to Basinski's wavelength or if the duo simply waited until the path to something lasting and beautiful organically revealed itself, I can confidently state that the pair ultimately wound up in exactly the right place regardless of how they got there. If I did not understand and appreciate the sizeable challenges inherent in crafting a hypnotically satisfying and immersive album from a mere handful of notes, I would be amused that Basinski and Schaefer first began working on this album together all the way back in 2014 and that the entire 8-year process basically resulted in just two or three simple piano melodies. In fact, I am still a little amused by this album's nearly decade-long gestation, but that does not make the result any less impressive. Significantly, " . . . on reflection " is dedicated to Harold Budd, but an even closer stylistic kindred spirit is Erik Satie (albeit a blearily impressionistic channeling of the visionary composer's work rather than any kind of straight homage).

There are several William Basinski albums that I absolutely love, but his various collaborations are rarely as compelling as his solo work (the leftfield Sparkle Division being a notable exception, of course). The fundamental issue is that Basinski's finest moments tend to be an intimate distillation of a single theme to its absolute essence, which does not leave much room at all for anyone else to add something without dispelling the fragile magic. While it is unclear if Janek Schaefer is unusually attuned to Basinski's wavelength or if the duo simply waited until the path to something lasting and beautiful organically revealed itself, I can confidently state that the pair ultimately wound up in exactly the right place regardless of how they got there. If I did not understand and appreciate the sizeable challenges inherent in crafting a hypnotically satisfying and immersive album from a mere handful of notes, I would be amused that Basinski and Schaefer first began working on this album together all the way back in 2014 and that the entire 8-year process basically resulted in just two or three simple piano melodies. In fact, I am still a little amused by this album's nearly decade-long gestation, but that does not make the result any less impressive. Significantly, " . . . on reflection " is dedicated to Harold Budd, but an even closer stylistic kindred spirit is Erik Satie (albeit a blearily impressionistic channeling of the visionary composer's work rather than any kind of straight homage). Previously based in Chicago, Steve Fors has build a small, but strong discography first as half of the duo the Golden Sores, and then on his own as Aeronaut. Now based in Switzerland, It's Nothing, but Still is his first full length solo work under his own name. It certainly feels like a new album, but traces of his previous projects can be heard, which is for the best. Lush with both beauty and darkness, it is nuanced and fascinating.

Previously based in Chicago, Steve Fors has build a small, but strong discography first as half of the duo the Golden Sores, and then on his own as Aeronaut. Now based in Switzerland, It's Nothing, but Still is his first full length solo work under his own name. It certainly feels like a new album, but traces of his previous projects can be heard, which is for the best. Lush with both beauty and darkness, it is nuanced and fascinating. Ten years after her first appearance on Keith Rankin and Seth Graham's perennially bizarre and eclectic Orange Milk label , Paul returns to the fold with her new trio. Naturally, there are plenty of similarities between this latest release and the trio's 2020 debut (Ray), but there has been some significant evolution as well. To my ears, I Am Fog feels considerably more sketchlike and challenging than Ray, but that is not necessarily a bad thing, as anyone seeking out an Ashley Paul album would presumably already have a healthy appreciation for dissonance and deconstruction. A decent analogy might be that Ray is like a short story collection while I Am Fog is more like a series of poems: the voice and vision are instantly recognizable, but these nine pieces are an unusually distilled, minimal, and impressionistic version of that voice. In less abstract terms, that means that I Am Fog again sounds like some kind of unsettling and psychotropic outsider cabaret, but the emphasis is now more upon gnarled/strangled textures and lingering uncomfortable harmonies than it is on melodic hooks and broken, lurching rhythms. In addition to the trio's overall step even further into the outré, the album also features further enticement with one of Paul's strongest "singles" to date ("Shivers").

Ten years after her first appearance on Keith Rankin and Seth Graham's perennially bizarre and eclectic Orange Milk label , Paul returns to the fold with her new trio. Naturally, there are plenty of similarities between this latest release and the trio's 2020 debut (Ray), but there has been some significant evolution as well. To my ears, I Am Fog feels considerably more sketchlike and challenging than Ray, but that is not necessarily a bad thing, as anyone seeking out an Ashley Paul album would presumably already have a healthy appreciation for dissonance and deconstruction. A decent analogy might be that Ray is like a short story collection while I Am Fog is more like a series of poems: the voice and vision are instantly recognizable, but these nine pieces are an unusually distilled, minimal, and impressionistic version of that voice. In less abstract terms, that means that I Am Fog again sounds like some kind of unsettling and psychotropic outsider cabaret, but the emphasis is now more upon gnarled/strangled textures and lingering uncomfortable harmonies than it is on melodic hooks and broken, lurching rhythms. In addition to the trio's overall step even further into the outré, the album also features further enticement with one of Paul's strongest "singles" to date ("Shivers"). Jeff Barsky has been quietly releasing alternately sublime and noise-ravaged guitar albums for years and this latest album finds him returning to LA's oft ahead-of-the-curve Already Dead Tapes (where he last surfaced with 2015's Flickering). Normally, I would not describe an edition of 100 tapes as a major release, but most of Barsky's solo work has historically appeared on his own Insect Fields imprint so Celestial Cycles will likely reach more ears than usual. Fittingly, it is an especially strong album, capturing Barsky at the absolute height of his powers. While few solo guitarists can summon dreamlike beauty from their ax as reliably and masterfully as Barsky, the centerpiece of this album is unquestionably the swirling and nightmarish closing epic "Become The Birds," which arguably recaptures the magic of Campbell Kneale's Birchville Cat Motel project in its prime (which is damn high praise coming from me).

Jeff Barsky has been quietly releasing alternately sublime and noise-ravaged guitar albums for years and this latest album finds him returning to LA's oft ahead-of-the-curve Already Dead Tapes (where he last surfaced with 2015's Flickering). Normally, I would not describe an edition of 100 tapes as a major release, but most of Barsky's solo work has historically appeared on his own Insect Fields imprint so Celestial Cycles will likely reach more ears than usual. Fittingly, it is an especially strong album, capturing Barsky at the absolute height of his powers. While few solo guitarists can summon dreamlike beauty from their ax as reliably and masterfully as Barsky, the centerpiece of this album is unquestionably the swirling and nightmarish closing epic "Become The Birds," which arguably recaptures the magic of Campbell Kneale's Birchville Cat Motel project in its prime (which is damn high praise coming from me).  I only recently heard Laura Cannell’s fabulous album The Earth With Her Crowns from 2020 and could easily spend 500 words praising its dazzling allure and stark—yet comforting—beauty. Time marches on, though, and since she already has two new releases in 2022 I am focusing on the present year. Both are excellent but, of the two, I am most immediately impressed by Antiphony, wherein Cannell uses alto, bass, and tenor recorders to riff on the birdsong of rural Suffolk , where she lives, which called to her amid the quietness of lockdown. It is riveting and a work that I am unlikely to set aside any time soon.

I only recently heard Laura Cannell’s fabulous album The Earth With Her Crowns from 2020 and could easily spend 500 words praising its dazzling allure and stark—yet comforting—beauty. Time marches on, though, and since she already has two new releases in 2022 I am focusing on the present year. Both are excellent but, of the two, I am most immediately impressed by Antiphony, wherein Cannell uses alto, bass, and tenor recorders to riff on the birdsong of rural Suffolk , where she lives, which called to her amid the quietness of lockdown. It is riveting and a work that I am unlikely to set aside any time soon.  On the trio's first album in seven years (the largest period of dormancy ever for them), Locrian simultaneously return to their origins while evolving and refining their sound forward. Stripped back to the barest essence of their sound but with some 17 years of evolution, New Catastrophism feels both like a reset but also a culmination of everything they have accomplished thus far.

On the trio's first album in seven years (the largest period of dormancy ever for them), Locrian simultaneously return to their origins while evolving and refining their sound forward. Stripped back to the barest essence of their sound but with some 17 years of evolution, New Catastrophism feels both like a reset but also a culmination of everything they have accomplished thus far. This latest release from the long-running ambient dub solo project of erstwhile Mi Ami/Black Eyes bassist Jacob Long is stirring up some feelings of regret about how I managed to sleep on this project for so long. While I am not yet sure if Ghost Poems simply caught me at the right time or if Long has been unusually inspired recently, my previous exposures to Earthen Sea left me feeling like the ambient/dub balance was too heavily weighted towards the "ambient" side to leave a deep impression. I suspect the balance has not changed all that much since I last checked in, but Long seems to have made a big leap forward in perfecting his execution with this album (it "further refines his fragile, fractured palette into fluttering arrythmias of dust, percussion, and yearning," according to the label). Apparently, I am very much into fluttering arrhythmias of yearning now, as the first half of this album boasts a handful of pieces that can stand with just about anything in Kranky's rich and influential discography: rather than resembling dub techno that has been deconstructed and dissolved into a soft-focus haze, Ghost Poems often feels like Long has managed to seamlessly combine the best of ambient and the best of dub techno into something fresh, wonderful, and uniquely his own.

This latest release from the long-running ambient dub solo project of erstwhile Mi Ami/Black Eyes bassist Jacob Long is stirring up some feelings of regret about how I managed to sleep on this project for so long. While I am not yet sure if Ghost Poems simply caught me at the right time or if Long has been unusually inspired recently, my previous exposures to Earthen Sea left me feeling like the ambient/dub balance was too heavily weighted towards the "ambient" side to leave a deep impression. I suspect the balance has not changed all that much since I last checked in, but Long seems to have made a big leap forward in perfecting his execution with this album (it "further refines his fragile, fractured palette into fluttering arrythmias of dust, percussion, and yearning," according to the label). Apparently, I am very much into fluttering arrhythmias of yearning now, as the first half of this album boasts a handful of pieces that can stand with just about anything in Kranky's rich and influential discography: rather than resembling dub techno that has been deconstructed and dissolved into a soft-focus haze, Ghost Poems often feels like Long has managed to seamlessly combine the best of ambient and the best of dub techno into something fresh, wonderful, and uniquely his own. Similar to his recent works Family Secret and House Blessing, the newest work from drummer/percussionist Jon Mueller features little in the way of overt rhythms or obvious instrumentation. Instead, The Future is Unlimited, Always captures Mueller at his most spacious: layers of frequencies and tones that are as engaging as they are mysterious, and capturing more than just audio, but a deeper sense of existence.

Similar to his recent works Family Secret and House Blessing, the newest work from drummer/percussionist Jon Mueller features little in the way of overt rhythms or obvious instrumentation. Instead, The Future is Unlimited, Always captures Mueller at his most spacious: layers of frequencies and tones that are as engaging as they are mysterious, and capturing more than just audio, but a deeper sense of existence. In general, releasing a three-hour album is a highly dubious endeavor, as such an extreme length usually turns even very good music into an endurance test and virtually guarantees that few people will ever listen to the entire opus more than once. When "Memphis dronegaze cult" Nonconnah do it, however, it feels like an absolute godsend. Part of that is because the husband/wife duo of Zachary and Denny Wilkerson Corsa lead what is possibly the most consistently fascinating and wonderful shoegaze/drone project around, but there is an equally important second part as well: the Corsas seem to be constantly collaborating with a host of talented guests. Unsurprisingly, that generates an ungodly amount of material and each major new Nonconnah album feels like a mere tantalizing glimpse into the innumerable killer jams and recording sessions that led up to the release. When I say that Don't Go Down to Lonesome Holler could have probably been an equally brilliant six- or nine-hour album, it is not hyperbole: there are over 50 credited performers involved in this album including folks from heavy hitters like Archers of Loaf, Swans, and No Age (as well as more than 60 instruments ranging from singing saws to cats). My guess is that the only limiting factor was how much time the Corsas could spend culling and editing their mountain of killer material without starting to lose their goddamn minds. This album is an absolute revelation ("Nonconnah's most comprehensive vision yet for the American halfpocalypse," according to the label).

In general, releasing a three-hour album is a highly dubious endeavor, as such an extreme length usually turns even very good music into an endurance test and virtually guarantees that few people will ever listen to the entire opus more than once. When "Memphis dronegaze cult" Nonconnah do it, however, it feels like an absolute godsend. Part of that is because the husband/wife duo of Zachary and Denny Wilkerson Corsa lead what is possibly the most consistently fascinating and wonderful shoegaze/drone project around, but there is an equally important second part as well: the Corsas seem to be constantly collaborating with a host of talented guests. Unsurprisingly, that generates an ungodly amount of material and each major new Nonconnah album feels like a mere tantalizing glimpse into the innumerable killer jams and recording sessions that led up to the release. When I say that Don't Go Down to Lonesome Holler could have probably been an equally brilliant six- or nine-hour album, it is not hyperbole: there are over 50 credited performers involved in this album including folks from heavy hitters like Archers of Loaf, Swans, and No Age (as well as more than 60 instruments ranging from singing saws to cats). My guess is that the only limiting factor was how much time the Corsas could spend culling and editing their mountain of killer material without starting to lose their goddamn minds. This album is an absolute revelation ("Nonconnah's most comprehensive vision yet for the American halfpocalypse," according to the label). Following a multitude of self-released tapes and digital releases, Vagrancies is Austin, Texas's Andrew Anderson's first CD based work. Ostensibly created by the instrumentation and sources listed in the disc's liner notes, Anderson's treatment renders them largely unidentifiable, instead using them to construct something else entirely. Consisting of four long-form pieces connected with shorter interludes, Vagrancies covers a lot of ground, with an impressive amount of variety from piece to piece, but still a strong sense of continuity from one piece to the next.

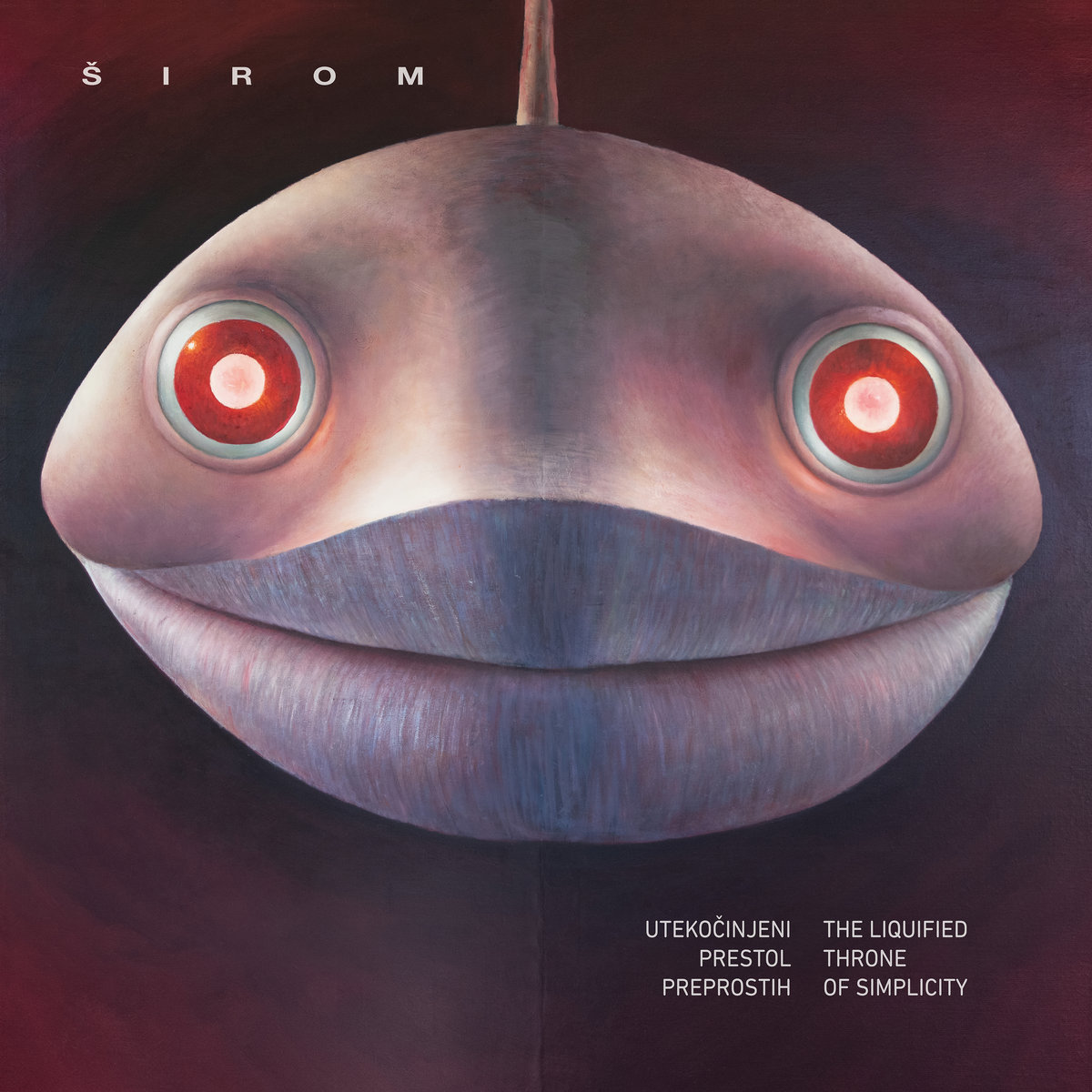

Following a multitude of self-released tapes and digital releases, Vagrancies is Austin, Texas's Andrew Anderson's first CD based work. Ostensibly created by the instrumentation and sources listed in the disc's liner notes, Anderson's treatment renders them largely unidentifiable, instead using them to construct something else entirely. Consisting of four long-form pieces connected with shorter interludes, Vagrancies covers a lot of ground, with an impressive amount of variety from piece to piece, but still a strong sense of continuity from one piece to the next. I feel like I got into this Slovenian "imaginary folk" trio a bit late, as 2019’s A Universe That Roasts Blossoms For A Horse was the first Širom album that I picked up. However, it also seems like each new album is the perfect time to discover Širom and those who join the party with this latest release are in for a real treat. Along with Belgium’s Merope and the scene centered around France’s Standard In-Fi and La Nòvia labels, Širom are one of the leading lights in a new wave of imaginative and adventurous international folk ensembles and this fourth album is their most expansive to date (“for the first time the trio…ignore the time constraints of a standard vinyl record to fashion longer, more fully developed entrancing and hypnotizing peregrinations”). Aside from making stellar use of their newly expanded song lengths, it feels like some delightful jazz influences have crept deeper into Širom’s DNA as well, as a couple of pieces feel like the various members trading wonderfully wild, visceral, and hallucinatory solos over strong, unconventional vamps (the album description also explicitly notes that Širom “echo the borderless, collective spirit of groups like Don Cherry's Organic Music Society and Art Ensemble of Chicago”). Obviously, that is enviable and excellent company to be associated with, but Širom’s influences transcend perceived boundaries of time and space so fluidly that trying to forensically determine the contents of their record collections is both hopeless and entirely beside the point. When they are at their best (which happens often here), Širom feel like a glimpse into an alternate timeline where the freewheeling adventurousness of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s never ended and everything just kept getting weirder, cooler, and more sophisticated forever (and record labels were delighted to foot the bill for anything that could potentially be the next The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter).

I feel like I got into this Slovenian "imaginary folk" trio a bit late, as 2019’s A Universe That Roasts Blossoms For A Horse was the first Širom album that I picked up. However, it also seems like each new album is the perfect time to discover Širom and those who join the party with this latest release are in for a real treat. Along with Belgium’s Merope and the scene centered around France’s Standard In-Fi and La Nòvia labels, Širom are one of the leading lights in a new wave of imaginative and adventurous international folk ensembles and this fourth album is their most expansive to date (“for the first time the trio…ignore the time constraints of a standard vinyl record to fashion longer, more fully developed entrancing and hypnotizing peregrinations”). Aside from making stellar use of their newly expanded song lengths, it feels like some delightful jazz influences have crept deeper into Širom’s DNA as well, as a couple of pieces feel like the various members trading wonderfully wild, visceral, and hallucinatory solos over strong, unconventional vamps (the album description also explicitly notes that Širom “echo the borderless, collective spirit of groups like Don Cherry's Organic Music Society and Art Ensemble of Chicago”). Obviously, that is enviable and excellent company to be associated with, but Širom’s influences transcend perceived boundaries of time and space so fluidly that trying to forensically determine the contents of their record collections is both hopeless and entirely beside the point. When they are at their best (which happens often here), Širom feel like a glimpse into an alternate timeline where the freewheeling adventurousness of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s never ended and everything just kept getting weirder, cooler, and more sophisticated forever (and record labels were delighted to foot the bill for anything that could potentially be the next The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter). This latest album from the consistently fascinating Atkinson is yet another plunge into a vibrantly textured and otherworldly dreamspace, this time drawing inspiration from an abstract dialog between house and landscape. Or more specifically, "Inside and outside, different ways of orienting a body towards the world." In keeping with that theme, Atkinson "revisited twentieth-century women artists who variously chose, and were chosen by, their homes as a place to work." Naturally, there are some other conceptual layers as well (this being a Félicia Atkinson album, after all). One of the more interesting ones is the decision to give the album a name that resembles a "fake title of a fake Godard film." In an obvious sense, that is apt given how Image Langage feels like a film with no actual images, but Godard's mischievous meaning-dissolving weirdness is also manifested in how Atkinson wields and repurposes her sounds. In more concrete terms, that means that Atkinson deliberately used instruments alternately like field recordings or characters in a murky, surreal narrative and often reduces her voice to an unpredictably drifting and elusive presence. The overall effect is like being lost in a beautiful dream where an unreliable narrator periodically drifts in with riddle-like non-clues that only lead me deeper into Atkinson's eerie, soft-focus enigma.

This latest album from the consistently fascinating Atkinson is yet another plunge into a vibrantly textured and otherworldly dreamspace, this time drawing inspiration from an abstract dialog between house and landscape. Or more specifically, "Inside and outside, different ways of orienting a body towards the world." In keeping with that theme, Atkinson "revisited twentieth-century women artists who variously chose, and were chosen by, their homes as a place to work." Naturally, there are some other conceptual layers as well (this being a Félicia Atkinson album, after all). One of the more interesting ones is the decision to give the album a name that resembles a "fake title of a fake Godard film." In an obvious sense, that is apt given how Image Langage feels like a film with no actual images, but Godard's mischievous meaning-dissolving weirdness is also manifested in how Atkinson wields and repurposes her sounds. In more concrete terms, that means that Atkinson deliberately used instruments alternately like field recordings or characters in a murky, surreal narrative and often reduces her voice to an unpredictably drifting and elusive presence. The overall effect is like being lost in a beautiful dream where an unreliable narrator periodically drifts in with riddle-like non-clues that only lead me deeper into Atkinson's eerie, soft-focus enigma.